In recent times, Positive Psychology has shifted the way we talk about mental health. While traditional approaches rightly focus on reducing symptoms and alleviating distress, positive psychology asks additional and essential questions: how do people move toward well-being, meaning, and fulfillment—especially after adversity; and, what do our adverse experiences give us that facilitate growth? Like the mythical Phoenix, humans have an innate capacity for healing and adapting to adverse experiences.

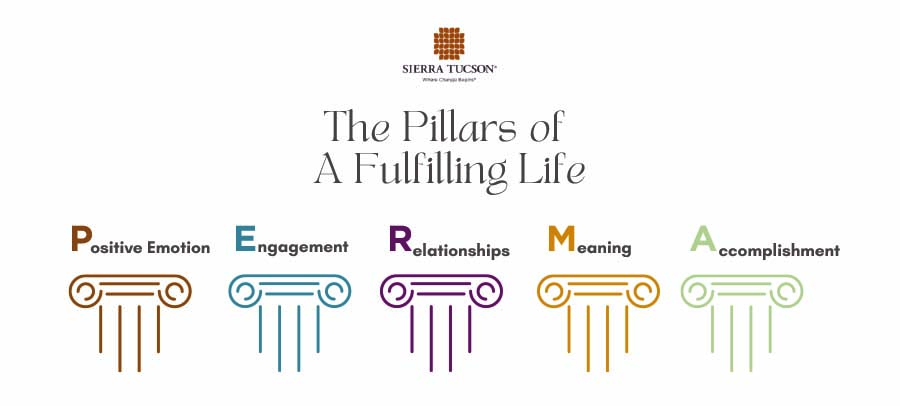

One of the most widely used frameworks in positive psychology is PERMA, developed by psychologist Martin Seligman. PERMA describes five pillars of well-being: Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Increasingly, this model is being applied to post-traumatic growth (PTG), a concept describing positive psychological changes that can occur following trauma.

Importantly, post-traumatic growth does not suggest that trauma is beneficial or that suffering should be minimized. Rather, it recognizes that growth and pain can coexist. PERMA offers a practical, compassionate framework for understanding where growth may occur as individuals heal.

Positive Emotion:

Making Room for More Than Survival

Positive emotion includes experiences such as joy, gratitude, interest, hope, or calm. Following trauma, emotional life can often center on fear, numbness, or sadness. From a trauma-informed perspective, the goal is not to dilute the validity of painful experiences, but rather to build an expanded emotional range.

Research shows that even brief moments of positive emotion can support nervous system regulation and cognitive flexibility (Fredrickson, 2001). In trauma recovery, positive emotion often appears in small ways: laughter, enjoying a small experience such as a good meal or peaceful sunset, or feeling a moment of relief. These experiences remind the brain and body that all is not lost, and that safety and pleasure are still possible.

Engagement:

Reconnecting with Presence and Strength

Engagement refers to a deeply present immersion in activities that grip our attention and can create a sense of “flow.” Flow can be described as a state of complete focus that energizes where one feels effective and can lessen self-consciousness. Trauma can impair this capacity by causing hypervigilance, dissociation, or exhaustion.

As healing progresses, many people rediscover activities that anchor them in the present moment—artistic endeavors, physical activity, seeking knowledge or time with nature. This can support recovery by shifting attention away from rumination on the past and onto the present, lived moment— helping us reconnect with strength and efficacy.

Relationships:

Healing and Deepening Connection

Relationships are the crux of both trauma and healing. Trauma often involves interpersonal wounds or leads to withdrawing from others. Post-traumatic growth includes meaningful shifts in how survivors relate to others, increasing empathy, maintaining more robust boundaries, and greater emotional attunement.

This does not mean someone has to gather a large circle of connections; rather, a few reliable and strong supportive connections offer opportunity for validation, co-regulation, and belonging—all essential to recovery. In fact, many experiences becoming more discerning and intentional about their connections following trauma.

Meaning:

Rebuilding a Sense of Purpose

Trauma can damage our perception of safety, justice, and self. Within the PERMA model, meaning refers to being a part of something greater than oneself. In post-traumatic growth, meaning is not about rationalizing harm, but about integrating experience into a larger self-story, where one can make something positive from the ashes.

Some find meaning through activities that contribute to a greater good, such as advocacy or volunteering. Others find they are able to sharpen their own awareness of personal values. Research suggests that meaning-making plays a central role in adjusting adaptively after trauma (Park, 2010). Importantly, meaning often surfaces gradually with perspective and cannot be rushed.

Accomplishment:

Restoring Agency and Confidence

Accomplishment involves setting goals and the resulting sense of competence. Trauma often renders one feeling powerless or feeble. Restoring a sense of achievement helps return one’s sense of agency.

In post-traumatic growth, accomplishments may be intensely personal: completing therapy, returning to work, setting boundaries, or navigating daily life with increased confidence. Every accomplishment reached affirms the belief, “I can act, choose, and move forward,” refuting shame and powerlessness.

PERMA as a Framework for Growth Following Trauma

PERMA does not take the place of trauma treatment. Likewise, growth does not occur in a linear manner across these five concepts. Survivors may notice growth in meaning before positive feelings return, or relational progress before a profound sense of achievement. The flexibility of this model makes it particularly helpful in trauma-informed care, as each individual story is unique.

By providing a framework of well-being versus pathology, PERMA allows individuals to envision existence beyond survival. It honors both the truth of suffering and humanity’s profound capacity for adaptation.

Trauma can change people— but it does not decide the limits of who they can heal and evolve into after. The PERMA model provides a hope restoring, evidence-based structure for understanding how well-being, connection, and purpose can return even after harrowing events.

Learn more at https://www.sierratucson.com

Kelli Parks, Interim Director of Clinical Services

Kelli Parks, Interim Director of Clinical Services

Kelli Parks is a specialty trauma therapist at Sierra Tucson who provides EMDR, trauma-focused CBT, and other integrated modalities to promote healing and traumatic growth. Kelli has worked in outpatient, inpatient, and residential settings since 2002. Kelli has worked with children and families connected with the child welfare system and worked with system partners to help those families heal. Kelli has worked extensively in the past with women experiencing postpartum mood disorders, as well. Kelli believes in a strength-based, holistic approach to recovery. She has a passion for maternal mental health as well as veteran and first responder mental health. Kelli received her BA in Psychology from the University of AZ and her Masters in Professional Counseling from Grand Canyon University,

In her free time, Kelli enjoys raising her two spirited girls with her husband, reading, weightlifting, and caring for their four rescue animals ( two dogs and two cats). When she has the time, Kelli likes to volunteer with local animal shelters.

References

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.